When I studied for my degree in Arts Education at Bretton Hall in Wakefield, we spent a lot of time exploring why the arts matter in schools — not as a “nice extra”, but as a powerful tool to help children learn, understand, and make sense of the world.

Over the years, there has been an increasing focus on measurable outcomes and core subjects. While literacy, numeracy, science and technology are clearly vital, however, education is about more than just passing tests. Children aren’t empty vessels to be filled with information and they aren’t robots being trained for productivity. They are curious, emotional, imaginative human beings who learn best when they are engaged, motivated and able to see the point of what they are doing.

During the pandemic, science and technology helped keep us safe and connected, but it was also stories, music, creativity, and shared culture that helped many people cope with isolation and uncertainty. That was a powerful reminder that the arts aren’t a luxury — they’re part of what makes us human.

Creativity isn’t separate from “serious” learning. In fact, real science, engineering and problem-solving all rely on imagination: asking “what if?”, trying things out, experimenting, and thinking in new ways. When learning becomes only about ticking boxes and memorising answers for tests children can lose that sense of curiosity and purpose. Creative approaches help bring meaning, motivation, and deeper understanding back into the classroom.

One of the most effective ways to do this is through learning-by-doing. Imagine pupils being asked to design a playground: they have to measure space, manage a budget, make decisions, explain their ideas and work together. Suddenly maths, literacy, design and problem-solving aren’t abstract — they’re tools for doing something real. Drama and storytelling can work in exactly the same way, placing learning inside a meaningful, memorable context.

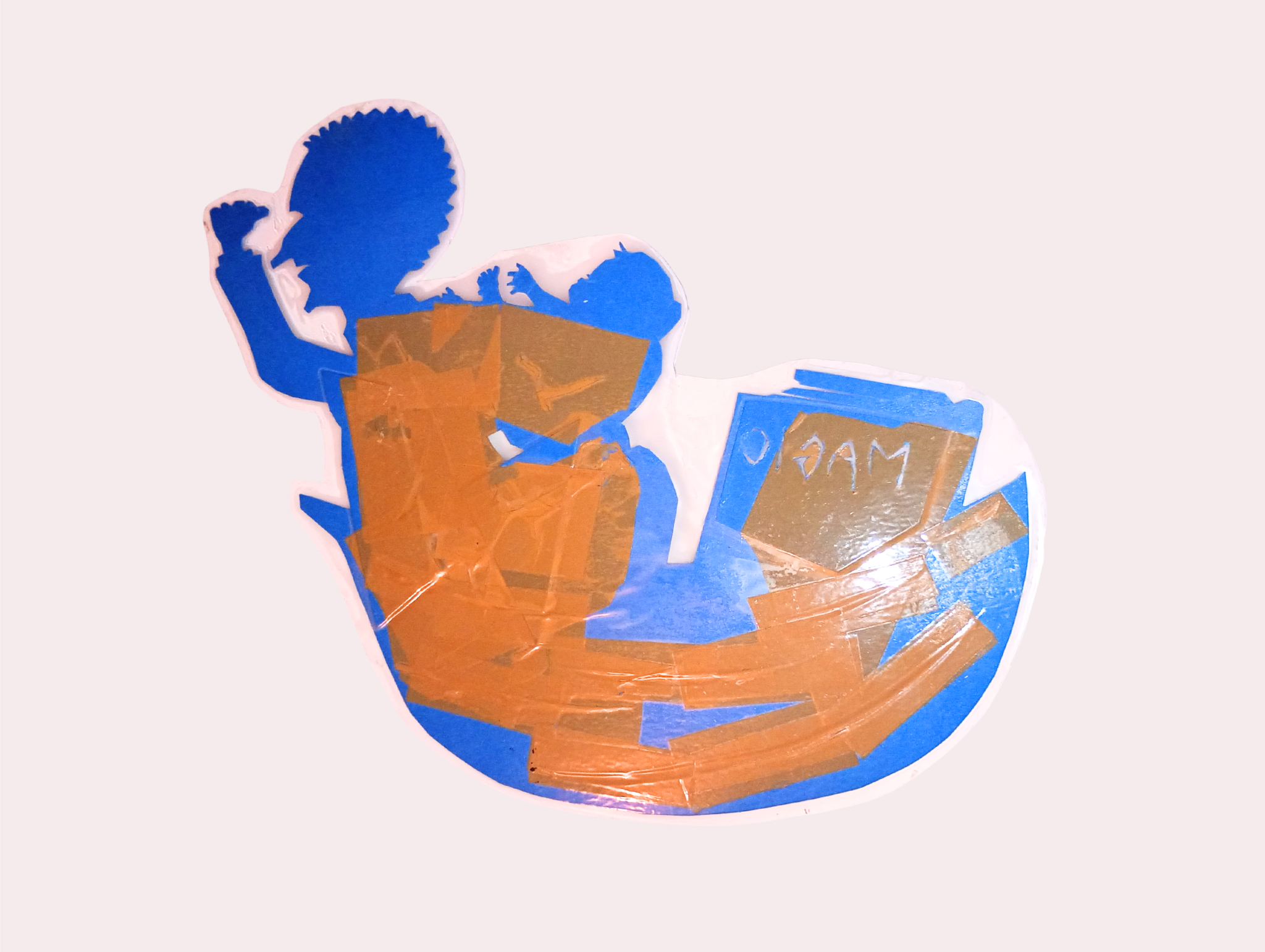

This is one of the reasons I love working with shadow puppetry in schools. It naturally brings together storytelling, art, design, performance, and teamwork — and it does so in a way that feels magical, playful, and accessible to children of all ages.

When you book a shadow puppetry performance and workshop with me, pupils don’t just watch a show — they take part in a rich, cross-curricular learning experience:

- Literacy & storytelling – creating characters, narratives, and performances, often linked to texts you are already studying

- Art & design – designing and making puppets, exploring silhouette, shape, and visual storytelling

- Science – discovering the properties of light and shadow, and how images change with distance, scale, and angle

- Teamwork & communication – working in groups as narrators, performers, and designers

- Fine motor skills – cutting, assembling, and manipulating puppets, supporting dexterity and hand–eye coordination

- Confidence & performance – presenting work to others and taking pride in something they have created

Perhaps most importantly, children have fun — and often don’t even realise how much they are learning while they’re doing it.

Shadow puppetry also shows pupils that they don’t need expensive equipment or electronic screens to tell powerful stories. With simple, inexpensive materials, they can go on creating their own shadow plays long after the workshop is over — developing creativity, confidence, and curiosity along the way.

For me, that’s what arts-based learning is really about: not just making something nice, but helping children discover new ways to think, express themselves, and engage with the world around them.